The Alresford Eel House

History and Habitat

The Eel House in about 1870

What’s it all about?

The Eel House at Alresford sits beside the Wayfarer’s Walk footpath (also now called the Arle Valley Trail) about a mile from the centre of the town: it straddles the River Alre, with a foot on each bank. The Alre is a chalk stream. There are about 210 chalk streams in the world, ¾ of them in England and most of those are in Southern England. In Hampshire we have three of the most iconic chalk streams in the world – the Test, Meon and Itchen respectively. The Alre flows into the Itchen, which goes through Winchester to enter the Solent in Southampton Water.

The surrounding area consists of white chalk, a form of limestone formed more than 60 million years ago, when the land was covered by a warm, shallow sea. The remains of countless marine creatures fell to the sea floor, where they slowly compressed into a sedimentary rock (chalk) and as sea levels fell, it became exposed. It is a relatively soft, porous rock, and natural forces have shaped it into the familiar rolling South Downs, which stretch almost 70 miles from Winchester in the west, to Eastbourne in the east.

Chalk can absorb large amounts of water (like a sponge), so forming vast underground reservoirs of water-bearing rock, known as aquifers. When this is saturated, water comes to the surface through springs – which is where chalk streams begin their journey. These have been renowned for centuries for their clear water and abundant wildlife.

From 1774 until 1812 William Harris owned much land to the West of Alresford (as explained by Jan Field of The Alresford Society in her 2019 book, An illustrated history of ‘The Big House’). You may have noticed Arlebury Park House on your left if you came here from Winchester. The 1807 Alresford Enclosure Award (a legal document confirming the boundaries of land holdings) shows that he owned about half of the agricultural land in Alresford. He sold the estate to Richard Bailey in 1812, who in turn sold it to John Rawlinson in 1814, including the land where the Eel House stands.

In about 1822 the estate’s owner commissioned this modest brick building with a tiled roof to trap mature eels near the start of their once-ina-lifetime journey. Tom Fort’s Book of Eels (2003) includes archaeological evidence that eels were part of the diet in some of the earliest known human settlements, near Lough Neagh in Northern Ireland, almost nine thousand years ago. The Domesday Book (1086) lists hundreds of watermills whose rent was paid in a specified quantity of eels. Records from the 14th century indicate that the church received thousands of eels a year in return for renting land and mills to others. As industrial cities grew in the 19th century, they needed large quantities of food: some landowners satisfied this demand by catching and delivering eels to market.

On moonless nights between September and December eels set off from the Alre and surrounding marshes, and make their way down to the River Itchen, into the English Channel and across the Atlantic. Their natural instinct is to return to their spawning grounds to breed – deep in the Sargasso Sea, between the Bahamas and Bermuda.

The Eel Trap

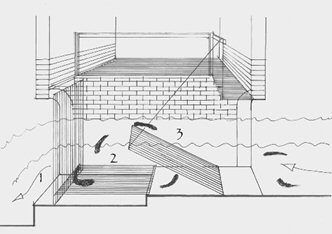

Three channels (culverts) run beneath the Eel House. The central one contains the trap, which consists of a vertical grill across the culvert at the downstream end (1) and a horizontal one along its bottom (2). The keeper pulled on a chain (3) to raise this horizontal grill to about 30 degrees: the eels wriggled up it and fell over the raised

The River Keeper lived a few yards downstream in Keeper’s Cottage in Drove Lane (replaced by a large, modern private residence in 2018,Drove House). Ray Fisher assisted the last River Keeper (Jim Collinson), and wrote in 2006:

Each autumn from 1967 to approximately 1980 the River Keeper and myself worked the Eel House to catch eels during the ‘dark quarters’ of the moon from September to December. On average we caught 50-60 pounds of eels each night we worked. These were kept alive in floating wooden crates just below the Eel House and then moved into oxygenated tanks.

The merchants would buy the eels and send them in the tanks by cart or lorry to Alresford Railway Station. Steam trains would take them to London, and then to Billingsgate Fish Market where, still alive, they were sold. Mr Fisher continued:

At the height of the eel catching season the River Keeper was paid up to £1 per pound for the live eels – a considerable addition to his salary. The owner allowed him to retain all the money on the understanding that the Eel House was kept in a good state of repair. When the river and houses were sold in the 1980s the Eel House was never again used, and fell into disrepair.